Workshop Guide to Transmission Trauma

By Steve Cooper, VJMC Editor

Someone once summed up gearboxes thus… “half of you know exactly what happens here and the other half are just glad that it does”. Most of us would agree with the sentiment but perhaps we knew more. Quite possibly only a small minority of classic Japanese aficionados actually have a good grasp on what goes on in those ink-dark depths somewhere towards the back of the engine.

If I’m honest, my grip on the situation was only tenuous; never having had a gearbox fail there was never any perceived need to go delving amongst the cogs, shaft, selectors and shims thereby unnecessarily opening a can of worms. The above quote prompted a little theoretical reading, which of course tempted fate just a just a tad too much.

Having sorted out an ongoing, daily rider project, an MOT was duly arranged, and bike and rider serenely motored on to the designated test station, although third gear seemed a little odd. The bike passed, and all seemed well until the gearbox demonstrated a marked reluctance to drop into third gear, latterly juddering like a demented road drill. Limping home, it was undoubtedly engine-out time once more. Calling on the services of my mate Peter, the engine was ripped apart and a tail of disaster unfurled. The gearbox (which I’d stupidly taken for granted) was comprehensively banjaxed.

The majority of Japanese/European gearboxes runs two shafts, both containing intermeshing gears (above) and selector drum and forks. The first, primary or input, shaft takes the motion from the engine/primary drive and transfers this to the next, secondary or output shaft with the gearbox output sprocket sitting on the end of this shaft.

Each pair of gears (i.e. a second input and a second output) is permanently engaged with each other, but one of each pair is capable of effectively freewheeling on one or other shaft. It’s not until the gear lever is pressed, that the freewheeling gear is pushed sideways engaging its dog-clutch gears, with a mirror image dog-clutch on another gear that is integral with the shaft; thus, second gear is engaged and we hop up from a fast run to some 20-30mph in progress terms.

Orchestrating the gear change is the gear pedal which moves the selector drum and the selector forks. The forks sit on their own shaft and move side to side as dictated by the grooves in the selector drum, selectively shuttling the gears as the rider decrees. All of this goes on under the protection of oil, which is generally only splash fed by what the gears pick up, although more modern machines have oil pumped to key areas.

If all goes according to plan, the gearbox seamlessly delivers bucket loads of torque to the rear wheel via the chain or shaft drive. Given just a modicum of care and consideration, an absence of water and the occasional oil change, gearboxes generally give little cause for concern; perhaps the maxim out of sight, out of mind, was never more appropriate or apocryphal. As we shall see, it pays to keep an eye on gearboxes and not to ignore the warning signs that may spell imminent doom.

The bike in question had led a hard life and had probably not received too much TLC. It had allegedly been laid up twenty-eight years ago when the clutch centre nut loosened. The lack of oil in the gearbox should have been ringing warning bells but as the engine had been partially dismantled to diagnose the clutch issue, it was assumed the lack of oil was due to the strip down.

On the end of the selector drum, there’s a non-ferrous thrust washer; the one on the far end of our selector drum was found to been worn seriously thin and this was one of the two issues that ultimately took out the gear train. This had allowed the drum far too much lateral movement, which in turn had allowed oil to be repeatedly forced into a blind bushing that supported the shaft in the engine case.

Ultimately the repeated hydraulic battering of the selector drum pushed out the hammered-in alloy plug in the gearbox casing, causing a perpetual oil leak and probably some very dodgy gear changes. It proved impossible to make the old alloy plug oil tight, so a new phosphor bronze plug was made and sealed in place with two-part epoxy; the plug can be seen at bottom right of the sprocket. Post rebuild, the fix has proved to be oil tight so it’s a good dodge to know.

Although these issues doubtless contributed to the gearbox’s demise, the actual root cause of the demonic hammering from third gear still remained to be determined. This is where a keen eye for detail and some good mechanical knowledge came in; never be afraid to call for some expert advice if you’re dealing with an area that’s new to you and the faults aren’t obvious. Good mate Peter and sage, old wily racer Graham, have seen more engine and gearbox issues than most of us and it was their expertise that pinned down a real problem.

The faces of most dog clutches are undercut; this means they are effectively machined at a shallow angle rather like a dovetail joint. The reason for doing this is to ensure that once the ratio has been engaged via the fixed and sliding cogs for any given gear, the two dogs are effectively pulled into each other by the undercut. If the dogs were cut parallel, there would be a tendency for the pair to separate, unless kept permanently under constant load.

As an example, on the road, this would manifest itself if you were hard on the power in third, had to throttle off briefly, then wound the throttle open again because there was no need to change into second. Without undercutting, chances are that the dogs would try to separate as you throttled off, taking the load off the driven gears. The selector fork would then try to keep the gears together and thus mechanical mayhem is perpetuated. Although the undercutting is only a few degrees, it’s key to maintaining drive.

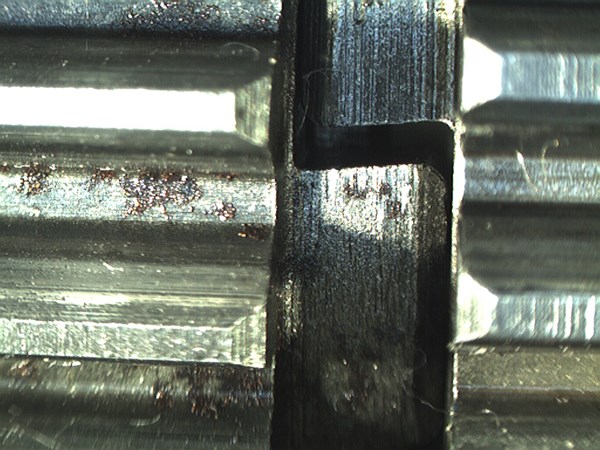

In our next shot we can see what good undercutting should look like. A few missed gear changes have little, if any, impact on the case hardening of gear, but long-term botched changes will inevitably take the leading tips off the dog clutches and from there it only a matter of time before serious wear sets in. Although the primary shaft and its gears looked OK, a serious squint of the output shaft showed a different story.

Focussing on third gear, it was possible to feel that when the two interconnected dogs twisted against each other, they were almost being repelled which is the complete opposite of what should happen. Doing the same with any other pair should clearly demonstrate the pull-in that undercutting is supposed to give, and this was exactly what happened. Close examination of the third gear dogs revealed a horror story that frankly defies belief.

A considerable amount of metal was missing from the leading edge of one of the dogs when compared to the face of the corresponding dog above it. Viewed straight on it might have been tempting to suggest it was only a missing tip, but when the gears were fully separated the full story was revealed. Not only was the tooth tip missing, but the metal behind had been fretted away and rounded off as the case hardening failed. The striations, or machining marks, to the left of the damaged area show what the dog’s face should have looked like. Although there was still an unmolested portion of undercutting, it was effectively negated by the missing metal.

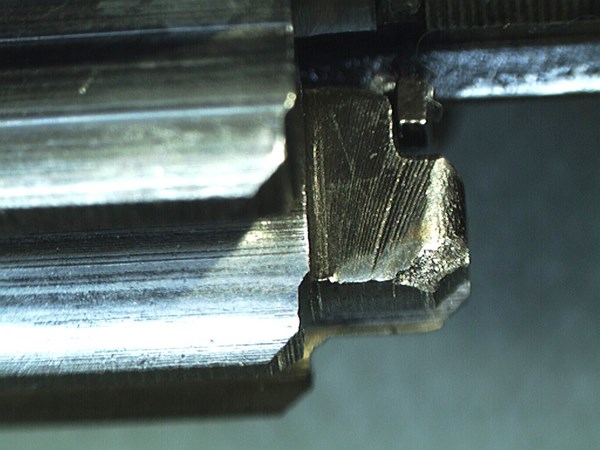

So that was it; two problems clearly identified and all we needed to do now was find the necessary spares to affect a viable repair. Although it had led a hard life, the selector drum checked out to be OK on the proviso that a new thrust washer was used. And then we looked at the selector forks. This piece of kit shouldn’t experience too much force in normal use.

The round stub on the right runs up and down the groove on the selector drum, providing lateral thrust to the fork allowing the two tabs, or prongs, of the forks to move the sliding gears side to side. Oil in the gearbox theoretically cools and lubricates everything. Looking at the picture it’s apparent that the flat tips of the fork had been worn down, and there was also wear in the outer strengthening ribs which worryingly suggested excessive movement; the shiny arc in the cleft of the fork screams something is really wrong. When you subsequently find that this fork is the better of the two, you begin to thank God the whole lot hadn’t let go when the bike was being ridden.

The second fork exhibited blueing indicative of severe overheating, and a close-up of the reverse side illustrates what happens when the case hardening breaks down. The coup de gras for the entire gear train was the crack that was spotted in the fork, across the point where maximum strain had been concentrated. If any further evidence was needed, an X-ray from the notional good side of the second selector fork clearly shows there’s a crack running top to bottom; this is how motors die.

With the undercutting missing in several places, two severely damaged selector forks and a selector drum that’s seen more than its fair share of abuse, it would be hard to convince anyone the rest of the gearbox was in a predictably safe and usable condition. It’s at a time like this that breakers, eBay, mates with similar old machines and auto jumblers come into their own. Buying a complete set of gearbox entrails from a main dealer (if still available) is never going to be cheap and even the classic specialists are unlikely to have everything you need at a bargain price, so I am indebted to Col for kindly turning up a low mileage gear train for £40; you are a star.

Next time any of us pull a wheelie it might be wise to remember just how much blind faith we place in our gearboxes; they may seem bulletproof but, as can be seen, they do fail. Thankfully the replacement parts are now installed, and the gear changes work as they should.

What I have subsequently found is that there’s a massive gap between third and fourth/top, which militates a lot of up and down the box toe-tapping when the bike is confronted with a headwind or significant gradient. This leads me to surmise that this may be one of the reasons why third gear has been so abused. Some years ago, I had similar issues with another machine and eventually overcame the issue of mismatched ratios by playing with the final drive sprockets. Looks like I have another workshop session on my hands then?

For more technical advice, visit Motorcycle Workshop Guides: The Complete List.

To find out more about a classic bike policy from Footman James and to get to an instant quote online, visit our Classic Bike Insurance page.

The information contained in this blog post is based on sources that we believe are reliable and should be understood as general information only. It is not intended to be taken as advice with respect to any specific or individual situation and cannot be relied upon as such.

COMMENT